Many new hands to embroidery are not aware of the rich history of embroidery samplers. Samplers are often percieved as nostalgic decorative pieces associated with interior decoration. In the past they have been a method of recording information about stitches, a way of learning stitches and before paper was plentiful a way of recording patterns. This brief history of Embroidery Samplers touches on the rich history of embroidery samplers that is hinted at in commercially produced patterns. Many stitchers enjoy working antique reproduction samplers, others work some samplers that depict Family trees, and commemorate events, such as weddings or births. Alphabet samplers and growth charts are also popular or samplers that record an life event, a right of passage, or some aspect of lived history. The function that samplers perform has however changed over time. One thing that remains constant however is that hand embroidery samplers have always been a record of stitches.

Many new hands to embroidery are not aware of the rich history of embroidery samplers. Samplers are often percieved as nostalgic decorative pieces associated with interior decoration. In the past they have been a method of recording information about stitches, a way of learning stitches and before paper was plentiful a way of recording patterns. This brief history of Embroidery Samplers touches on the rich history of embroidery samplers that is hinted at in commercially produced patterns. Many stitchers enjoy working antique reproduction samplers, others work some samplers that depict Family trees, and commemorate events, such as weddings or births. Alphabet samplers and growth charts are also popular or samplers that record an life event, a right of passage, or some aspect of lived history. The function that samplers perform has however changed over time. One thing that remains constant however is that hand embroidery samplers have always been a record of stitches.

The word exampler or sampler is derived from the French exemplaire, meaning a kind of model or pattern to copy or imitate. The Latin word exemplum, meaning a copy, was, by the 16th century, spelt saumpler, sampler or exemplar.

Before printed pattern books, embroidery designs were passed from hand to hand, many travelling through Europe from the Middle East. The recording of patterns and motifs on fabric for future use was not only needed to learn the stitches but it was also an essential method of storing information. This stitched reference resulted in the creation of a sampler. New patterns and stitches were avidly collected and exchanged. Early in the history of embroidery samplers patterns were placed in a haphazard way over the cloth. These samplers are now referred to as random or spot samplers.

The collection of patterns accelerated in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. There are a number of factors that may explain the sudden explosion of the enthusiasm that associated with recording patterns at this time. In the late 15th and early 16th centuries needlework decorated clothing and furnishings. The craft of embroidery was restricted to the wealthy due to the high cost of materials and that by the early 16th century needlework had gained importance as embroidery displayed wealth and status. In the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries there was also a strong revival of interest in all forms of decoration and a sudden increase in travel at this time.

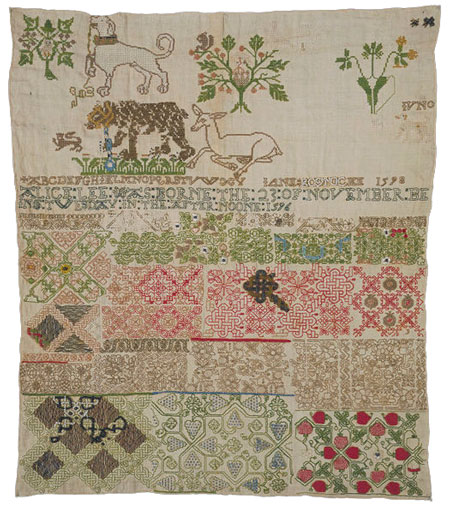

The earliest surviving sampler which is signed and dated, was made by Jane Bostocke who included the date 1598 in the inscription. You can see more of this famous sampler on the V&A website here. However the earliest documentary reference to sampler making is recorded in 1502. The household expense accounts of Queen Elizabeth of York record that: ‘the tenth day of July to Thomas Fisshe in reward for bringing of concerve of cherys from London to Windsore . . . and for an elne of Iynnyn cloth for a sampler for the Quene’.

Band samplers what are they?

English samplers of the sixteenth-century were worked in a long narrow ribbons. The width being 6-9in (15-23cm). The length was determined by the loom width of the woven linen cloth. The Anna Buckett sampler dated 1656 is an example of this type of sampler. This sampler is held in the Met Museum collection and if you visit their site you can see the details by clicking on the image

Since fabric was expensive, band samplers are often totally filled with designs. To the modern eye they can appear crowded but sampler devotees love the visual textures these patterns can create. We know that these samplers were valued at the time of making them because they were often mentioned in royal inventories and bequeathed by will.

Modern interpretations of samplers are often worked in cross stitch alone. This was not always the case, band samplers of the sixteenth century often combined different stitch traditions such as Blackwork, Assisi work and complicated bands of whitework and open-work. The samplers of this period display such a high standard of work it is believed that they were created by expert needlewomen. Excellent use of a large variety of stitches worked in silk and metal threads produced beautiful designs. Geometric patterns worked in as many as twenty different colours were combined with spot motifs of flowers, animals, birds, insects, fish, and frogs.

Some of the numerous stitches used were Hungarian, Florentine, tent, cross, long-armed cross, two-sided Italian cross, rice, running, double running, Algerian eye and buttonhole stitches. Colour schemes with a large number of shades were created by twisting together strands of two different colours.

The demand for printed patterns for needlework was eventually exploited commercially and the first printed pattern book arrived in 1523, printed in Augsburg, Germany, by Johann Sibmacher. Similar books then appeared from French and Italian presses and finally in England from 1587. However pattern books were not readily available and samplers continued to be made as practice pieces and for reference.

During the 17th Century, a very simple border was added to the sampler to surround a number of randomly placed motifs. The band sampler, however, remained popular; the bands consisting of geometrical and floral designs in repeating border patterns. By the middle of the 17th century, alphabets were included in samplers. It has been argued that this indicates that sampler-making was becoming more significant as an educational exercise. Borders had also become more elaborate. From about 1650 moral and religious inscriptions were often added. Around this time samplers became signs of virtue and achievement and the teaching of needlework in schools was actively encouraged.

Samplers of the 18th and 19th centuries were in complete contrast to the random spot and band samplers of earlier times. During the 18th century, samplers took on the proportions of a picture. Symmetrically placed motifs of birds, small animals, flowers and trees were arranged to produce a balanced picture. Samplers, having lost much of their utilitarian function, had become ornamental, and were displayed as a record of achievement.

Stitching the alphabet began in the 17th century. By the 19th century, samplers were well established as vehicles for religious instruction, geography, English and mathematics. School girls produced needlework exercises of almanacs, mathematical tables and maps, as well as numbers and letters.

From about 1770, map samplers were worked. These samplers were considered an excellent way of teaching geography although most were inaccurate, because the children copied and drew the outlines themselves. Traces of the rich history of samplers can still be found in commercially produced patterns which idealise the values of the past. Under Victorian ideology, women, when embroidering for their own pleasure, were accused of vanity. The notion of embroidery as a ‘vain’ and merely decorative occupation undermines the expressive power of embroidery. Today, hand embroidery is still defined as a leisure-time activity. Their making was also a reflection of the growing interest in foreign travel.

Although Medieval embroidery involved both men and women in guild workshops, and was considered to be equal to painting and sculpture the Victorians re-wrote the histories of the craft. Victorian historians meshed history with ideologies of femininity and inferred that embroidery had always been an inherently female craft. Understanding this recast view of history of embroidery is crucial to understanding how twentieth-century attitudes to the needle arts were shaped.

Over the centuries the reasons for working samplers have changed, as have the design sources. The print media, for instance, influenced sampler design with the increased circulation of engraved illustrations. In the past, old herbals had been a design source. With the rise of the middle class, and the consequent spread of formal garden design, knot garden patterns became a strong design influence on samplers.

Today the internet has influenced the development of samplers and how they are designed. Enthusiasts have used the technology to teach and inspire others to use hand embroidery stitches and of course many stitchers use a sampler to learn so although they may interpret the stitches in modern manner they are in fact very much working in the tradition.

I hope you have enjoyed my brief overview and history of embroidery samplers. If you want to see my own band sampler which is a quirky project I have fun with. As I write this my sampler is nearly 100 feet long. That is not a typo – as it is made of different strips of fabric that are stitched together to form one long strip. You can read about how it came to be made and why and its details on the Sampler FAQ page Here you can see my band sampler exhibited in 2014 at the Embroiderers Guild ACT exhibition. You can get a sense of how long it is as you can see I trouble fitting it in the frame!

Thread Twisties!

Experimenting with different threads can be expensive, as you would normally have to buy a whole skein of each type of thread. So I have made up my thread twisties which are a combination of different threads to use in creative hand embroidery. These enable you to try out stitching with something other than stranded cotton. For the price of just a few skeins, you can experiment with a bundle of threads of luscious colours and many different textures.

These are creative embroiders threads. With them, I hope to encourage you to experiment. Each Twistie is a thread bundle containing silk, cotton, rayon and wool. Threads range from extra fine (the same thickness as 1 strand of embroidery floss) to chunky couchable textured yarns. All threads have a soft and manageable drape so that twisting them around a needle makes experimental hand embroidery an interesting journey rather than a battle. Many are hand dyed by me. All are threads I use. You may find a similar thread twist but no two are identical.

You will find my thread twisties in the Pintangle shop here.

Really interested in your comments on initials on samplers – is that a Scottish trait/characteristic for samplers?

Also mine has 2 crowns? is there any significance in that.

It also has a castle and i wonder if this has relevance to where the sampler was embroidered

Thanks

Kath Wpoodley

Hi Kath the crown is usually a reference to royalty ie what reign the sampler was made in. Or sometimes there are more than one crown they can be there just for decoration, particularly on modern samplers. Initials on samplers are not tied to nationality. I have seen them on British, Scottish, American, Australian samplers.

I live in New Zealand & I have been researching a Scots branch of my family tree for some years. Jean Ritchie (b.1809 Blair Atholl, Perthshire) was my 3x great grandmother. Some years ago I networked with another NZ descendant & she sent me a copy of a cross stitch sampler Jean stitched in abt 1821. It includes the usual designs for that period… an alphabet, numbers 1-12, Jean’s name & age & other pictorial images. But the 3rd & 4th lines include a series of initials, some of which are stitched in black thread.

I’m trying to interpret these as a possible aid in obtaining more info on Jean’s family, grandparents etc. It has been suggested that the initials in black may be deceased grandparents?

I’d really appreciate it if you are able to help me.

Jane I sent you an email – if it does not turn up check your spam

Yes I did get your email. Thanks for your suggestions. I’ve contacted the website link you suggested. It looks like the name initials could b interpreted using the Scottish naming system. I haven’t managed to do that yet.

Hi, thank you for this article. I’m French and I just wanted to make a correction: éxamplair is not correct. The word is writtern : exemplaire (no “é” before an “x” + takes an “e” at the end)

Thanks corrected it!

Fascinating! Do you know of any samplers that have heart figures in them? If so, could you send me the reference? I would be very grateful

Marilyn Yalom

maryalom@gmail.com

Hi there

I have a wall hanging I guess it’s like a sampler with all the alphabet and in the squares there are pics that match the letters and it also has numbers embroided from 1-10 seems to be done on some kind of animal all around the edge is hair from an animal ,maybe a deer hide was told it is possibly 16th century,quite an amazing piece of art if I were to send you a photo could you maybe tell me something about it thanks Donna.k

Donna take it to an expert- perhaps in a museum – as I am sure they will be able to tell you more than I could from a photo

I recently inherited my great-grandmother’s sampler, worked when she was 13 years old in the early 1890s. On the advice of my friend who is a museum conservator, I had it framed archivally to preserve it as much as possible. The thread and fabric is disintegrating in places. Another friend who is a weaver has offered to copy the linen fabric so that I can reproduce the work in modern materials.

Sounds wonderful – and you are treating it well – I always promise myself to do a reproduction sampler but have yet to do it- or at least have a section of my band sampler as reproduction bands. having the right count linen would be wonderful – you have a good friend there!

Thanks Sharon. I have always loved Samplers. My 80 yr old neighbour has a framed sampler on her wall, worked by Ursula Strickland, age 15. She asked me if I could do her family tree so we could find Ursula. Thanks to all the data that is on-line these days we traced back to her g-g-g-grandmother, Ursula Strickland, born 1798. Samplers play a part in genealogy, too.

I had not considered how Samplers played a roll in tracking family history and womens history but of course you are right – they are a valuable historical document.

Really fascinating. I had no idea that the Victorians reconstructed the gendered nature of embroidery. That has certainly resulted in history being rewritten. Thanks for a really interesting article

Aileen they also classified stitches too – into what became needlepoint (Berlin work), pulled, drawn, goldwork, blackwork, ribbon embroidery, surface embroidery etc

What a wonderful article! I wish I could see your sampler in person.

And what a scandalous thing to do; taking a piece of your hard work!

You are so inspiring!

Pleased you liked the article – I have always found samplers interesting